“Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” — Walter Benjamin

Early January this year, my girlfriend and I visited Paris. We were only there for two days, and, as it was my first time in the city, our itinerary was stuffed with all of the things one feels one must do when visiting Paris — the Eiffel Tower, Notre-Dame, the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée de l’Orangerie — and, of course, the Musée du Louvre.

The Louvre is the archetypal museum — when one thinks of a museum, one thinks of the Louvre. The place itself — those stark glass pyramids against the ornamented buildings that surround them — is a symbol of art as much as the pieces contained within it are. Whilst the Orsay has a more interesting collection, and the Orangerie is more serene, it is the Louvre which seems to say “You are now Looking At Art.”

There is, however, one piece of art in the Louvre which says this more so than the building itself — Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. Say the word “art” to an eight-year-old, she will likely think of this painting. It has been reproduced ad infinitum — if I were discussing any other painting, I would now place an image of it into the post: with the Mona Lisa, there seems no point.

Upon arriving in Paris, we dumped our bags at the apartment in which we were staying, and immediately made our way to the Louvre. We were eager to Look At Art.

In the main hall of the Louvre are entrances into the various wings of the museum, each labelled with names that gave little away as to what was within. We could have found ourselves a map and navigated the place sensibly, but we let chance guide our visit — we picked a wing at random, and wandered in. There wasn’t much in particular that we wanted to see at the Louvre — aside from the Mona Lisa, that is.

The wing we found ourselves in contained the Louvre’s ancient Egyptian collection — a fascinating exhibit, but we found — after about an hour — that there are only so many sphinxes, sarcophagi & eye-hieroglyphs that one can see on any given day, and we returned to the main hall.

Starting to feel hungry, and still tired from the flight over, we decided we’d go see the Mona Lisa, whatever pieces we encountered along the way, and then leave.

Not wanting to leave it to chance again, my girlfriend went to the information desk to find out which wing the Mona Lisa was in. Not only were we told which wing, but which floor, and where to go on that floor. Easy — we’d make a beeline for the piece, and then go grab some food.

Once in the appropriate wing, we began to see signs leading us towards Leonardo’s masterpiece. Even easier. Just follow the signs — we’d be there in no time.

However, each sign seemed to lead only to another sign. And then another. Soon, we were back where we started. And then we found that the signs contradicted each other. This one says left, but that one before said that it was right. Is that one pointing downstairs, or just to the left? I’m pretty sure this sign is pointing towards an emergency exit.

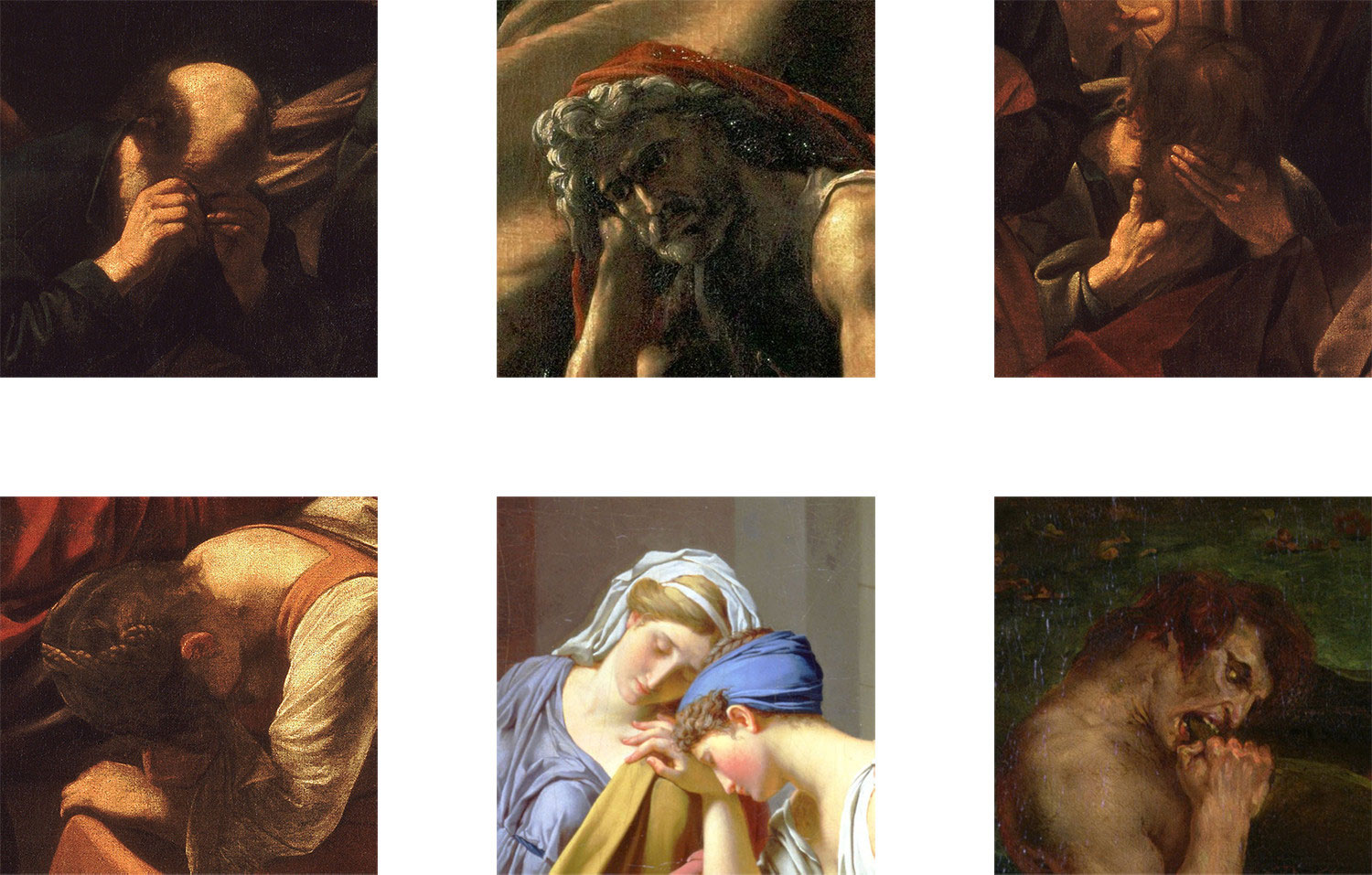

By this point, we had probably been looking for half an hour. We’d seen lots of nice art along the way, but now, it was starting to feel like every painting we saw was of us — each face painted centuries ago to reflect back at us our frustration and desperation.

In my tired, hungry, angry-at-the-Louvre state, I began to wonder — what if she isn’t here? What if that’s the point? Maybe there’s a great worldwide conspiracy and we’re now the latest to learn of it — that the Mona Lisa doesn’t exist. She exists only as reproduction. There is no original.

I knew it was a fanciful idea, but decided to follow it nonetheless. The Mona Lisa that we think of is not the one that hangs in the Louvre anyway. We are fascinated by the reproduction — by the fame that that reproduction brings. The real Mona Lisa — however masterful it may be — is just a painting. The only reason people want to look at the original — the reason that people fly halfway around the world just to see it — is in the hope that this experience will allow them to see the reproduction in a new way.

Brian Eggleston says of the Mona Lisa:

Where once it was a painting of a woman with a slightly odd smile, now it is no such thing at all. It has ceased to be a painting of a woman, and has become a painting of itself.

I might go one further — the Mona Lisa is now not even a painting of itself, but a painting of art in its entirety. It is a symbol for the institution that promotes genius as a commodity, that turns a thing of beauty into a thing that one must “understand”, that has made this 77 × 53 centimetre poplar board coated in oil paint worth more than, well, just about anything.

In 1911, the Mona Lisa was stolen by Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia — it sat in his apartment for 2 years before being found and returned to the museum. Throughout those two years, people still flocked to the Louvre to gaze at the blank space of wall where the Mona Lisa had once been. Billy Parrott suggests that it did not matter to those who went to see it whether the painting was there — everybody had seen its reproduction countless times before. What mattered was people being seen looking at it:

People standing in line, looking at an empty space on the wall. People looking at other people look at the empty space on the wall. Everyone knowing what should be there. Everyone knowing exactly what the thing would look like.

All this is not to say that there is no value in seeing the original Mona Lisa — there is, but to get to that value, one has to strip away all of the myth around her — what John Berger would call “bogus religiosity.” Instead, we have to learn to see the painting as simply that: a painting. A woman, as seen by a man, in a culture very different from our own. A man, trying to share with others that which he saw as beautiful.

Eventually, we found her. There she was, on a wall all by herself — the Mona Lisa. The original. A wall of bulletproof glass surrounded her, and a wall of tourists surrounded that. People shuffled around, trying to get closer to her, spending more time looking at their own personal reproductions of the painting in their phones that at the painting itself. They (and also we) were focused not on the Mona Lisa, but on how, by reproducing it, they would be seen by others as having looked at it. In the end, the Mona Lisa was in the Louvre — but maybe we weren’t.